The gap between what would be necessary in times of climate change and what is actually being implemented is wide. “Over 311 million rural mountain people in developing countries live in areas exposed to progressive land degradation, 178 million of whom are considered vulnerable to food insecurity,” the United Nations announced on today’s International Mountain Day. “This problem affects us all. We must reduce our carbon footprint and take care of these natural treasures.”

The reality is different. At the UN Climate Change Conference (COP 28), which ends tomorrow (Tuesday), the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) is set to veto all formulations aimed at reducing fossil fuels, as the “undue and disproportionate pressure” could reach a tipping point “with irreversible consequences”, as stated in a letter from OPEC Secretary General Haitham al-Ghais to all members of the oil cartel. Perhaps the oil sheikhs should be sent to the Himalayas so that they can get an idea of the already obvious consequences of climate change on the mountain regions.

Rapid glacier melt

According to a study published last summer by the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), glaciers in the Hindu Kush, Karakoram and Himalayas are expected to shrink by 30 to 50 percent by 2100 – given a temperature increase of between 1.5 and two degrees Celsius compared to pre-industrial times. Scientists currently assume that temperatures could even rise by 2.4 to 2.7 degrees Celsius by the end of the century.

A study published last week from the Everest region should also set alarm bells ringing – even if at first glance it may seem like a glimmer of hope in the gloomy world of climate change forecasts.

Cold downwinds in the Everest Valley

An international research team led by Italian Francesca Pellicciotti analyzed the weather data that had been collected near the “Pyramid” over the past three decades. The research station was set up in 1990 near the settlement of Lobuche in the Everest Valley at an altitude of around 5,000 meters. Despite climate change, the values on the ground surface in the valley of the Khumbu Glacier have remained surprisingly stable since 1994.

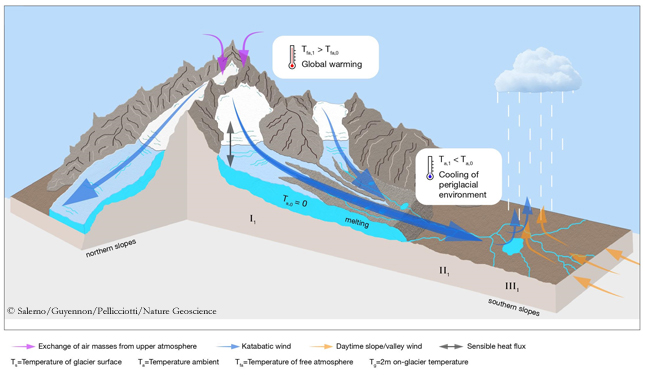

The scientists’ explanation: the peaks are warming up faster. The glaciers react to the rising temperatures of the surrounding air by increasing their temperature exchange with the surface. This creates cold fall winds, so-called katabatic winds, that blow down the mountain slopes and cool the lower parts of the glaciers.

No alternative to less CO2 emissions

“This phenomenon could help preserve the permafrost and surrounding vegetation,” says Nicolas Guyennon, who was part of the research team. “While other glaciers are experiencing dramatic changes right now, the glaciers in High-Mountain Asia – the Third Pole – are very large, hold more ice masses, and have longer response times. Thus, we might still have a chance to ‘save’ these glaciers,” explain the scientists. However, this can only succeed if CO2 emissions are drastically reduced.

The katabatic winds also ensure that precipitation shifts to lower regions. As a result, the already melting glaciers are lacking a supply of mass. The perceived cool temperatures flowing down from glaciers are an emergency reaction to global warming rather than an indicator of glacier long-term stability.

The cold downwinds on Everest remind me of the phenomenon of emergency flowering of plants under stress – like a desperate cry for help from glaciers in dire need. I fear that the decision-makers at the UN Climate Change Conference in Dubai are deaf on the mountain ear. Listen up, damn it!