Climate change is increasingly throwing a monkey wrench in the works of even top climbers: heavy precipitation at times when it used to be dry, high temperatures where it used to be cold, falling rocks and avalanches. Graham Zimmerman was among those who returned empty-handed from the Karakoram last summer.

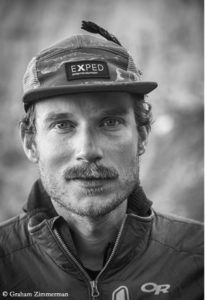

Zimmerman is a U.S. citizen and a New Zealander: He was born in Wellington, his American parents returned to the U.S. when he was four years old, Zimmerman later studied in New Zealand and now lives in Bend in the U.S. state of Oregon. The 35-year-old is one of the best alpinists in the world. In 2014 he was nominated for the Piolet d’Or for his new route via the Northeast Buttress of Mount Laurens in Alaska (together with Mark Allen), and in 2020 he received the “Oscar of the Climbers” (together with Steve Swenson, Chris Wright and Mark Richey) for the first ascent of the seven-thousander Link Sar in the Karakoram. Zimmerman’s film about the pioneering feat in summer 2019 was just released (see video below). Graham answered my questions about the impact of climate change on climbing the world’s highest mountains.

Graham, last summer you and Ian Welstedt attempted to climb K2 via a new variation of the West Ridge route. You stopped at about 7,000 meters because of the climatic conditions on the mountain. What exactly did these look like?

At 7000m the route transitioned from a well defined ridge crest to a series of buttresses threaded by gullies. This created a decision making point after which we were not longer able to ride the ridge and were subject to dramatically more over head hazard.

Generally speaking my experience has shown that above 6500m day time temperatures are low enough that climbing during the day is safe. But at the crucial 7000m juncture we were seeing shaded temperatures of 14+ degrees Celsius.

This was causing massive shedding events (both rock fall and wet avalanches) that were pouring down the mountain around our little safe spot perched on the ridge. With warmer weather in the forecast it was an easy decision to bail.

You have been in the Karakoram several times before in the summer season, for example in 2015 you opened a new route on the seven-thousander K6 or in 2019 you were among the climbers who succeeded in the first ascent of the seven-thousander Link Sar. Has the weather in the Karakoram become more unpredictable after your experiences?

I have been climbing in the range for 7-8 years which is a small sample size but scientists are showing that the range is warming and are indicating that a stronger monsoon is making for a less predictable weather. This is all of course directly associated with human driven climate change. My experience in the range anecdotally supports these findings.

Climbing high mountains on well-trodden paths is not your thing. You try your hand at unclimbed mountains and new, challenging routes in clean style. Have such ambitious projects become even more difficult in times of climate change?

This is an interesting question and the answer is certainly yes since a big part of attempting first ascents in the big mountains is understanding what you can and can not control. With more out of our control (due to climate change and it’s associated geopolitical effects) it’s harder but at the same time, we’re there for a challenge. In turn we come home with stories that can be used to drive the political change that’s needed to address these issues.

What conclusions do you draw from the failure on K2? Have you buried your eight-thousander ambitions?

This is a hard question. I’ve not yet decided the next objective but I remain deeply inspired by climbing hard in big mountains.

You call yourself (on your website and social media) a “climate advocate”. As such, what advice do you give to climbers?

As climbers we are directly interfacing with the high altitude and high latitude parts of the world. These are the parts of our planet most effected by climate change. They are the “Canaries in the coal mine” if you will. So we should pay attention and use our stories as tools to drive the systemic change that we need in order to manage out carbon emissions.

For my part I work with (the NGO) Protect Our Winters to help drive that systemic change.