Many reporters, including myself, just didn’t have him on their Everest radar. This spring, Rasmus Kragh tackled the highest mountain on earth for the third time without bottled oxygen. In 2017 and 2018, the Danish professional climber had tried to scale Mount Everest via the Tibetan north side of the mountain and had turned around at 8,600 meters each. Last spring, the 30-year-old climbed via the Nepalese south side – and was successful. On 23 May, Kragh reached the highest point at 8,850 meters, as the first Dane without breathing mask. Rasmus comes from the town of Aarhus on the east coast of Denmark. Two months after his Everest adventure he answered my questions.

Rasmus, you reached the summit of Mount Everest on 23 May – according to your own words without bottled oxygen. Did you use it neither during ascent nor during descent?

Without the use of supplementary oxygen means without supplementary oxygen at all. I have never taken a sip of a bottle, and didn’t do it neither during ascent nor descent, on Mount Everest this year.

Did you carry bottled oxygen for the case of emergency?

I didn’t carry any emergency oxygen. I’ve turned around two times previously on the north side of Everest in 2017-18, due to bad weather. And I would do it again, rather than using bottled oxygen. In my opinion it’s a false safety to give yourself the opportunity of taking bottled oxygen. You might end up pushing yourself too close to and maybe even over the limit, if you know that you can rely on a bottle somewhere, to save you if you need it. Then I’d rather stay in control without, and if it means that I’ll have to turn around, I’ll do so. Hypothetically. That’s my principles.

What was your tactic to avoid traffic jams on the summit ridge like on 22 May?

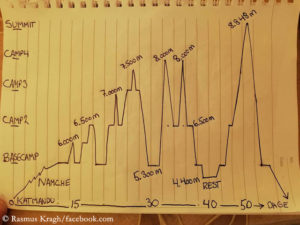

Already in Camp 1 could see the massive crowds move up towards Camp 2. They would all plan for the 21st, 22nd or 23rd as summit days. So I decided to move up to Camp 2, with the option of going for the summit on the 22nd – which would mean no rest day in Camp 2, or I could take a rest day and shoot for the 23rd. I had a hope that the masses would go for the 21st, and then I could go for 22nd with still an extra day on the 23rd left of the predicted weather window. Well, when I was in Camp 2, it became clear to me that the majority anyway would move on for the 22nd. I saw them move up the Lhotse Face towards Camp 3. A very big line of people!

So I simply decided to let them go. I knew instantly that this could result in trouble and traffic jams higher up. My biggest fear regarding a summit push without bottled oxygen on the south side of Everest has always been the risks created by other people on the mountain. And here it was presented to me up-front. If I end up queuing on the summit ridge of Everest, it would mean that I’d have to turn around, or risk dying.

Besides avoiding the greatest number of people, it was also an important part of my tactics to start out earlier from South Col. So I left Camp 4 around 7.30 pm on the 22nd. I could have left even earlier, but I also knew that the last part of my tactics could and would make up for it: Climb fast, but remain control! I stood on the summit at 6.50 am, it took me around 11 hours and 20 min to climb to the summit. I was back at South Col again at 11.30 am, making it a 16 hours roundtrip.

It was your third attempt on Everest without bottled oxygen. In 2017 and 2018, you turned back at 8,600 meters. What have you done differently this time?

Well, first of all the weather was good on my summit day, 23 May this year. It wasn’t in 2017 and 2018. Besides of that, I have gradually been optimizing, improving and generally been professionalizing my setup. This year I was able to dedicate myself fully to the cause and do it as a fulltime professional athlete. That means that I was able to train twice a day during my physical preparations, and focus my time and resources on the task ahead of me. That was a result of sponsor support that finally came around, and was able to cover my expedition and most of my everyday living expenses. I also had a very dedicated and professional team around me. They did all the media-work and live-coverage on Social Media and our website throughout the expedition. And I even had a guy with me in base camp that was dedicated to help me out, hence giving me the opportunity to increase my focus on the mission – climbing the mountain. The guy is also a master in sports science and works daily as a coach, so he did a great job optimizing me as an athlete.

My experience from the two previous attempts has also played a very important role. I knew what to expect, I knew how to respond to extreme altitudes, and I knew which acclimatization plan would work out and do the job for me. And at last – I was better prepared physically than ever before.

How did you prepare for the ascent without bottled oxygen?

Well, that’s a very broad question. But to make the answer short, the amount of training and personal resources that I put into it was equivalent to how many Olympic athletes prepare for the Olympics. I’ve focused on endurance training, with mostly running and cycling (I have my roots as a former elite-runner during my teenage years), and then a big amount of specific and heavy strength training. Mostly training twice a day, and living as a professional athlete. I’ve collaborated with my personal coach for the past two and a half years, and we’ve developed a recipe to train for the specific task of climbing Everest without O’s. This year I also got my mental coach onboard in my team what made a great difference in my focus and mindset. Besides that, I also had a light training program which I followed during my rest days in base camp – to stay strong and to avoid too much deterioration.

There has been much discussion about whether the number of people on Everest should be limited. How do you feel about that?

That’s a tricky question. Because the freedom in the mountains is for everyone. The freedom to choose your own goal and pursue it in the way that motivates you the most. If you limit the numbers, you’ll limit that freedom.

Instead of just limiting the numbers I believe more in a system where you need to have a certain level of experience before you can obtain a climbing permit for Everest. Like when you apply for a job, and a minimum level of education and/or experience are required before you get considered of being a relevant candidate.

Make a system where you cannot obtain a climbing permit for Everest unless you have climbed a 7.000 and an 8.000 meter peak. Then the numbers on Everest will decrease automatically. You could also use a system like that to promote other Himalayan and Nepali peaks, with the benefit of the Nepali government not loosing money on the falling numbers of issued Everest permits, because the money will just be paid according to increasing traffic on other peaks.

What do you feel now when you think back to the time on Everest?

I’ve spent the last four years of my life dedicated to Mount Everest, and the mission of climbing it in control and without the use of bottled oxygen. It has been a fantastic journey indeed. But also a true rollercoaster ride of emotions.

It has changed me as a person and given me a new perspective on life. And it will take some time to digest all the experiences, and my reflections have honestly just begun. Everest and my journey there with three following seasons spent on the slopes will forever be a part of me.

But I also feel like I need a break from the mountain. I need to go elsewhere, because I’m kind of filled up with the place. It feels like Everest has become a little too familiar, with all its beauty and all its human traffic and increasing commercialization. Now is the time for me to write and finish my book, do a lot of speeches and to set myself new goals as an athlete.

Really good article, helping give Rasmus Kragh the kudos he deserves. To keep going back for another try, twice, makes him even more of a champion than success on his first go!